Kuching – An old town for newcomers!

All cities have their own mythologies. They announce an idea of their grand and special status to every newcomer, declaring their character through vaulted train stations, impressive edifices or triumphal arches. But Kuching, only 200 years old, is itself the city of the newcomer: a city of Brunei noblemen coming to control a territory, of adventurous immigrants looking for a new life, of an English family establishing a new country, of colonial powers expanding their territories. So many newcomers have found their homes here and that is the feeling for many first-time travellers, a homecoming to a place they have never before visited. It is a warm welcome to a close-knit community made up of many such newcomers who have found their way over its history and are here to stay.

For Kuching, our announcement of the city is the neat, square Fort Margherita, unexpectedly built in the style of a European medieval fortress complete with mini battlements by the Second Rajah of Sarawak and named for his English wife. It became the first sight of the city as early travellers made their way up the Sarawak river, the usual port of entry, and it told a story of both aspiration and assimilation. Finished in 1879, just sixty years after the establishment of Kuching as a settlement and just 35 years after the formation of the nation, it was an announcement to the world that Sarawak was here to last.

A Time of Transformation

This was a time of transformation in the Rajah’s still tiny town. Charles Brooke, who succeeded his uncle as Rajah in 1868, announced in April of that year that all the ‘unsightly and insecure’ wooden and atap roof shophouses that once made up the Main Bazaar should be replaced by bricks and mortar. Initially ignored, an unusual occurrence for the resolute Rajah, he reissued the order in 1871 and work commenced. As the Sarawak Gazette describes: ‘the old tumbledown abodes, inhabited for the most part by the poorer artisans among the Chinese have given place to neat plank houses roofed with bilian, and built with the same approach to regularity.’ In the end, initial slow progress was rapidly accelerated when 135 houses on Main Bazaar and Carpenter Street behind it were razed to the ground by in the Great Fire of Kuching in 1884 and the two streets that we see today truly came into being.

In the midst of all this change, Margherita went up. Sarawak was settled and the Rajah secure in his seat. So why the tiny fort that has never seen a single shot fired? In fact, it was a show of solidity, an announcement in all its Englishness that this fledgling independent nation could compete on the world stage. The Rajah had been pained that the first sight of colourful painted houses on the way into Kuching was ‘in no way impressive’ to visitors and so he built the sturdy fort to make a different first impression. In the end, this proclamation of a new nation has become a reminder of its longevity. Today, it houses the Brooke Gallery, a mini museum dedicated to the Brooke era, set up by a Brooke descendant; always worth a visit via the Brooke period’s preferred mode of transportation, the perahu tambang or river taxi.

The First Wave of the New

The river that these traditional ‘taxis’ cross has always defined Kuching. It flows from its rocky upper reaches in the jungles of Padawan out to the South China Sea at Muara Tebas and it has brought in newcomers of all kinds. This river which gave its name to the State was presumably the draw which saw Pengiran Indera Makhota establish the settlement in the 1820s. From here, this high-ranking official of the Brunei Sultanate oversaw the management of Sarawak Proper. The indigenous people lived elsewhere, the Sarawak Malay in their seat upriver at Lidah Tanah, alongside the Bidayuh, and so Kuching was itself the newcomer. It was a small town, established for trade and taxation, and as with most incipient cities, it drew in yet more newcomers, most notably perhaps its future, first Rajah, James Brooke, who sailed up the river from Singapore in 1839 and made Kuching his capital. Whether he seized or settled Sarawak is still up for debate, but either way, little remains of James Brooke’s reign except for an idea.

But that idea is everything. From his capital, he brought in a Sarawak of industry and of the rule of law, and most importantly of equality, whether incomer or indigenous. He brought in new people and with them new beliefs, new practices, new flavours, new punishments and a new age of security for Sarawak to flourish. It is this Sarawak that you can see today in Kuching, from the Tua Pek Kong temple at one end, the oldest in Kuching, at the edge of the Chinese quarter, stretching out into India Street. In this space, mosques, shophouses, temples, opium dens, clan associations, churches, traders, kampungs, spice shops and markets grew up, cheek by jowl, the typical melting pot of the East.

A Connected Kuching

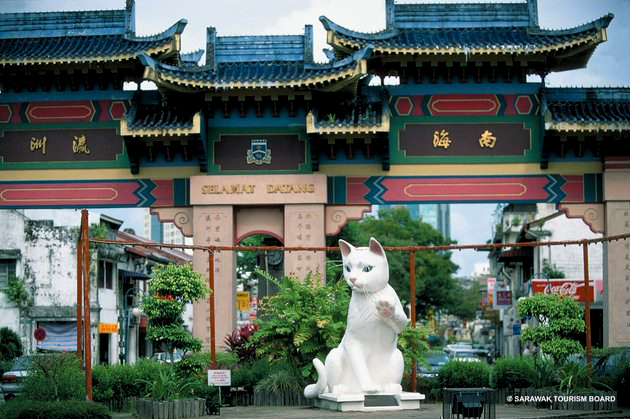

The Pintu Gerbang (Gateway) are Kuching’s triumphal arches and they tell the story in themselves. The last, at the far end of Jalan Padungan right next to Kuching’s iconic giant cat statue is connected to the second at the far end of Carpenter Street, and these mark the transition from Chinese characters and temple tiles, through the Japanese building of the Courthouse, the only structure purpose-built during the Japanese Occupation, all the way down to the Islamic lines of the entrance at the start of India Street. The whole of Kuching culture is contained between these arches, standing shoulder to shoulder, in one long seamless line. In between are the buildings of the Brooke administration, the glue that stuck these several parts together into the Sarawak we see today.

This stroll through Kuching’s varied yet harmonious history assumes a start at the Fort, making your way downhill for a wander through beautiful Kampung Boyan, many of its residents drawn there by the reign of the Rajahs. The Borneo Company, set up in 1856 to “take over and work Mines, Ores, Veins or Seams of all descriptions of Minerals in the Island of Borneo, and to barter or sell the produce of such workings” had its office on the modern day site of the Hilton and the whole waterfront was a mess of markets, godowns and jetties for goods coming down river and then out into the great beyond. There was work in a settled Kuching which brought many settlers.

Come the Chinese

A quick hop across by river taxi, traditional in every way except for the low growl of the outboard motor instead of the slow sweep of the oars, the Waterfront awaits, now a long, promenade for locals and visitors alike. It offers tiny Chinese pagodas along its length and the Chinese Chamber of Commerce building. This was built by Charles Brooke in 1912 as a courthouse for the growing Chinese population to settle their business matters, as the carving of the scales of justice above the door attests. It now houses a Chinese History Museum, telling the tale of this immigrant group who transformed Sarawak’s economy.

It was Charles that really encouraged the Chinese into Sarawak. James had accepted the influx of Hakka Chinese miners into upriver Bau from neighbouring Kalimantan as the Dutch took that territory, but that had ended in an uprising that almost lost him his head, so he was understandably wary. But Charles, who held a horror of allowing a European planter class, knew that the industry of the Chinese instead would fill his coffers and so, in the 1870s, he offered inducements for them to come to his new nation. Free passage from Singapore to gambier and pepper planters, land for their use and, of course, an affordable supply of opium meant that they came in their droves.

The whole area adjoining the Waterfront began to flourish with their traditional trades. The carpenters set up in Carpenter Street, many of the signs declaring a special Shanghainese origin, though in reality, the majority were Hokkien speakers. But multiple language groups also arrived – the street houses a Hainanese temple to MaZu, the Goddess of the Sea, as well as a Teo Chew temple further down which once staged traditional opera for the gods. Tin smiths, traders, food vendors, fishermen, farmers, rickshaw pullers, goldsmiths and apothecaries flourished, giving the area a character which remains to this day. The opium dens which once whiled the hours away at Kai Joo Lane, however, have long since shut up shop.

The Courthouse at the Centre

Whether you opt for the wide-open space of the waterfront or the warren that is the streets behind, the journey takes you next into the heart of the Brooke administration, to the building that straddles the Chinese centre and India Street beyond it. The Old Courthouse is the heart of Kuching, now a venue for food, drink and tourism, inviting in newcomers of a new era. But it is an example of all that has been said so far about Sarawak harmony. It was completed in 1874 by Rajah Charles, a decade after it was initiated by James before him and it tells you all you need to know about the nation they built.

Actually the third Kuching courthouse, it was built in a Sarawak hybrid style, using local materials and a mix of indigenous architecture – a belian shingle Malay hip roof covers verandas from an Indian tradition, shaded by projected eaves referenced from Dayak longhouses, all put together with the skill of local carpenters. Most importantly, it was always open on all sides, a metaphor for Brooke justice, housing the Court, the native court, government offices and the Council Negri, Sarawak’s multi-ethnic country’s multi-ethnic legislative assembly, right up until the early 1970s. There is a memorial directly in front, erected in 1924 by the third Rajah, Charles Vyner Brooke in honour of his father in 1917. It’s four sides depict reliefs of the main ethnic groups in Sarawak – Chinese, Dayak, Orang Ulu and Malay – all joined at the hip, as it were!

All around it are a cluster of Brooke buildings; the dispensary directly adjacent, and the Pavillion behind that, Kuching’s original skyscraper at two storeys and its first hospital, now turned into the Textile Museum. The Post Office opposite came in under Vyner, a neo-classical confection topped by the Brooke crest, but also the mile marker for the rest of the town that now spiralled out around it. Just across river stands the Astana, Rajah Charles’s home and another gift to his new bride in 1870, completing the great triangle of power, protection and administration. Stories say that Rajah Charles would watch his officers through a telescope to tell if they came to work on time, an endeavour assisted by the addition of a convenient clocktower on the front of the Courthouse.

Added spice from the Indian Subcontinent

On the opposite side of this blended building lie two new communities, linked by this long stretch of river. The first is evidenced in India Street, a haven of textile shops that are a long thread between Kuching and the Indian Subcontinent. Again, the second Rajah had a hand in it all, bringing in a small community of expertise for a range of activities from tending his horses to policing the nation to taking care of his tea plantation. The Indian Muslim community set up trade in central Kuching and gave their name to the street. In a tiny laneway connecting India Street to Gambier Street hides a small mosque, its presence announced by the architecturally unique spice shops that scent the air on the way in. This land which housed a small surau was sold to the community in 1871 by Rajah Charles for the ‘inhabitants of Sarawak who profess Mohamadean religion not being Malays’, and then the mosque constructed in its place in 1876.

The percentage of Sarawakians of Indian extraction remains small in comparison to Semenanjung, though still significant. When the Rajah’s tea plantation closed, only about half of the Indian families, 40 in number, chose to remain and these were the seed of Sarawak’s Hindus, their temples scattered throughout Kuching and even as far afield as Mount Matang. The Sikh temple is much closer by to India Street, still serving free vegetarian food every Sunday for all and sundry. Meanwhile, the Indian Muslims have outgrown their original mosque and a new structure stands like a swan on the Sarawak River, alight at night across from the Astana, a reminder of just how far this community has come.

The advent of modernity

But the more iconic mosque in Kuching is a Sarawak sunset. Kuching City mosque is one of the city’s most photographed structures, blush pink topped with gilded domes and the next stop along the way. This Masjid Lama or Old Mosque replaced a wooden original in 1968 that had stood on the site since 1852, and it is still a gateway between the city’s early attempts at modernity and the traditions of Kuching’s Malay community. Just opposite is an open space and a ramshackle wooden shed, a far cry from the grandeur of most city centre train terminuses around the world. This was once the station for Sarawak’s only train track, plying its route from the city centre out the straight run to 10th Mile. With three engines, fondly named Bulan (Moon), Bintang (Star) and, unexpectedly, Jean, powered by coal from Sadong colliery, the railway was Rajah Charles’s passion project, which ran from 1916. But roads eclipsed rail and this new entry into the city was eventually abandoned.

More successful in modernity was Brooke Dockyard opposite it, trading on the State’s maritime and riverine character. This massive dry dock, a feat of engineering in itself, was opened in 1912 by Vyner Brooke, the third Rajah, and his wife Sylvia, who gave her name to the town’s first cinema. In fact, the site is still in working order, along with the company that owns it. The city centre operation has largely moved out of town but the canary yellow steam crane and the power hammer inside the steel structure, imported all the way from England, await a rebirth as a mooted maritime museum.

The Sarawak Malays make Kuching their own

But behind the mosque, away from the thud of heavy machinery and the modern hum of traffic, is the peace and quiet of another Malay community, preserved as it has been since the early days of the city. The Sarawak Malays have a long history of collaboration with the Brooke family, supporting the first Rajah against the Brunei Sultanate, saving the city from insurrection by marauding miners and then building the multi-cultural state that exists today. One of the first houses past the mosque is the aptly named Rumah Batu (Stone House). While its glories are somewhat faded, it too embodies an idea.

As the first Malay house built in bricks and mortar in 1863, it gave up many of the traditions of indigenous architecture, taking its cues instead from the Rajah’s third house, though of course adapted to accommodate a large extended family. It was the house of Abang Kassim and demonstrated his prominent position, progressive politics and his relationship of equal status with the Rajah. This was the Sarawak that thrived, with the Rajah’s relying entirely on a local agency, independent almost entirely from the UK’s influence, building a new nation based on a collaboration that was almost unheard of in this era.But, while Rumah Batu set the tone for many Sarawak buildings that followed it, the kampung that stretches out behind it, in fact six kampungs seamlessly sprawling into one, is a return to form. This is traditional Malay life. Mini motorbikes whizz by laden with passengers; roadside stalls sell Malay delicacies; families stay close as the land divides and new houses come up side by side. It is a step away into an enclave of calm, full of timber houses, some with Minangkabau roofs, next to more modern family homes, but the common factor is the community that lives within them.

Cession, colonisation and the making of Malaysia

At the end of the long road that begins with Rumah Batu is a glorious example of a traditional Malay house, raised on pillars and projecting outwards into a pristine garden of neatly clipped lawn and spreading shrubs. Darul Maziah was built in the late 1880s by Haji Hassim Arif, who served as the herald to Charles Vyner Brooke, Sarawak’s third and final Rajah. In front is a tall pillar of wood, carved with Jawi script which tells a story of the end of the Brooke Raj and the transition to new rule.

Stories say that this pillar was erected by the anti-cession movement, a marker of their rejection of colonisation by the British government. Following the Japanese Occupation, Sarawak became Britain’s final territorial acquisition as Vyner ceded the independent nation to the Crown, a move that would lay the foundation for the formation of Malaysia just two decades later. In 1946, Sarawak became a colony for the first time in its history and saw a whole new host of newcomers. Perhaps for the first time, Sarawak was less than welcoming to the incomers, seeking instead the return of the Rajah or ideally its own independence. Mass resignations by the civil service were followed by massive protests on the streets of cities throughout Sarawak, a movement which only ended in the shock following the assassination of the newly-appointed British Governor, Duncan Stewart, as he toured Sibu. This marked the end of an era, as the British secured their stronghold and a new colonial administration came into play and this humble wooden marker is a small reminder.

Kuching continues on

Nevertheless, the spirit of Kuching was already settled. The advent of every outsider has only served to strengthen that. It is the city of the newcomer who can always find a welcome and a place to call home. After two centuries of acceptance, regardless of race, religion or place of origin, a strange harmony is at its heart, giving Kuching the title of Malaysia’s first ‘City of Unity’, an accolade officially received in 2013 but secretly held since it started. For every traveller looking for a place to hang up their hat and put up their feet in a new home, Kuching is your city. This is our heritage. But beware; once you have been once, you will yearn to return!

Written by: Karen Sherpherd